The post Six Insights on Preference Signals for AI Training appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

At the intersection of rapid advancements in generative AI and our ongoing strategy refresh, we’ve been deeply engaged in researching, analyzing, and fostering conversations about AI and value alignment. Our goal is to ensure that our legal and technical infrastructure remains robust and suitable in this rapidly evolving landscape.

In these uncertain times, one thing is clear: there is an urgent need to develop new, nuanced approaches to digital sharing. This is Creative Commons’ speciality and we’re ready to take on this challenge by exploring a possible intervention in the AI space: preference signals.

Understanding Preference Signals

We’ve previously discussed preference signals, but let’s revisit this concept. Preference signals would empower creators to indicate the terms by which their work can or cannot be used for AI training. Preference signals would represent a range of creator preferences, all rooted in the shared values that inspired the Creative Commons (CC) licenses. At the moment, preference signals are not meant to be legally enforceable. Instead, they aim to define a new vocabulary and establish new norms for sharing and reuse in the world of generative AI.

For instance, a preference signal might be “Don’t train,” “Train, but disclose that you trained on my content,” or even “Train, only if using renewable energy sources.”

Why Do We Need New Tools for Expressing Creator Preferences?

Empowering creators to be able to signal how they wish their content to be used to train generative AI models is crucial for several reasons:

- The use of openly available content within generative AI models may not necessarily be consistent with creators’ intention in openly sharing, especially when that sharing took place before the public launch and proliferation of generative AI.

- With generative AI, unanticipated uses of creator content are happening at scale, by a handful of powerful commercial players concentrated in a very small part of the world.

- Copyright is likely not the right framework for defining the rules of this newly formed ecosystem. As the CC licenses exist within the framework of copyright, they are also not the correct tools to prevent or limit uses of content to train generative AI. We also believe that a binary opt-in or opt-out system of contributing content to AI models is not nuanced enough to represent the spectrum of choice a creator may wish to exercise.

We’re in the research phase of exploring what a system of preference signals could look like and over the next several months, we’ll be hosting more roundtables and workshops to discuss and get feedback from a range of stakeholders. In June, we took a big step forward by organizing our most focused and dedicated conversation about preference signals in New York City, hosted by the Engelberg Center at NYU.

Six Highlights from Our NYC Workshop on Preference Signals

- Creative Commons as a Movement

Creative Commons is a global movement, making us uniquely positioned to tackle what sharing means in the context of generative AI. We understand the importance of stewarding the commons and the balance between human creation and public sharing.

- Defining a New Social Contract

Designing tools for sharing in an AI-driven era involves collectively defining a new social contract for the digital commons. This process is essential for maintaining a healthy and collaborative community. Just as the CC licenses gave options for creators beyond no rights reserved and all rights reserved, preference signals have the potential to define a spectrum of sharing preferences in the context of AI that goes beyond the binary options of opt-in or opt-out.

- Communicating Values and Consent

Should preference signals communicate individual values and principles such as equity and fairness? Adding content to the commons with a CC license is an act of communicating values; should preference signals do the same? Workshop participants emphasized the need for mechanisms that support informed consent by both the creator and user.

- Supporting Creators and Strengthening the Commons

The most obvious and prevalent use case for preference signals is to limit use of content within generative AI models to protect artists and creators. There is also the paradox that users may want to benefit from more relaxed creator preferences than they are willing to grant to other users when it comes to their content. We believe that preference signals that meet the sector-specific needs of creators and users, as well as social and community-driven norms that continue to strengthen the commons, are not mutually exclusive.

- Tagging AI-Generated vs. Human-Created Content

While tags for AI-generated content are becoming common, what about tags for human-created content? The general goal of preference signals should be to foster the commons and encourage more human creativity and sharing. For many, discussions about AI are inherently discussions about labor issues and a risk of exploitation. At this time, the law has no concept of “lovingly human”, since humanness has been taken for granted until now. Is “lovingly human” the new “non-commercial”? Generative AI models also force us to consider what it means to be a creator, especially as most digital creative tools will soon be driven by AI. Is there a specific set of activities that need to be protected in the process of creating and sharing? How do we address human and generative AI collaboration inputs and outputs?

- Prioritizing AI for the Public Good

We must ensure that AI benefits everyone. Increased public investment and participatory governance of AI are vital. Large commercial entities should provide a public benefit in exchange for using creator content for training purposes. We cannot rely on commercial players to set forth industry norms that influence the future of the open commons.

Next Steps

Moving forward, our success will depend on expanded and representative community consultations. Over the coming months, we will:

- Continue to convene our community members globally to gather input in this rapidly developing area;

- Continue to consult with legal and technical experts to consider feasible approaches;

- Actively engage with the interconnected initiatives of other civil society organizations whose priorities are aligned with ours;

- Define the use cases for which a preference signals framework would be most effective;

- Prototype openly and transparently, seeking feedback and input along the way to shape what the framework could look like;

- Build and strengthen the partnerships best suited to help us carry this work forward.

These high-level steps are just the beginning. Our hope is to be piloting a framework within the next year. Watch this space as we explore and share more details and plans. We’re grateful to Morrison Foerster for providing support for the workshop in New York.

Join us by supporting this ongoing work

You have the power to make a difference in a way that suits you best. By donating to CC, you are not only helping us continue our vital work, but you also benefit from tax-deductible contributions. Making your gift is simple – just click here. Thank you for your support.

The post Six Insights on Preference Signals for AI Training appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post CC Responds to the United States Copyright Office Notice of Inquiry on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>Since our founding, we have sought out ways that new technologies can serve the public good, and we believe that generative AI can be a powerful tool to enhance human creativity and to benefit the commons. At the same time, we also recognize that it carries with it the risk of bringing about significant harm. We used this opportunity to explain to the Copyright Office why we believe that the proper application of copyright law can guide the development and use of generative AI in ways that serve the public and to highlight what we have learned from our community through the consultations we have held throughout 2023 and at our recent Global Summit about both the risks and opportunities that generative AI holds.

In this post we summarize the key point of our submission, namely:

- AI training generally constitutes fair use

- Copyright should protect AI outputs with significant human creative input

- The substantial standard similarity should apply to Infringement by AI outputs

- Creators should be able to express their preferences

- Copyright cannot solve everything related to generative AI

AI training generally constitutes fair use

We believe that, in general, training generative AI constitutes fair use under current U.S. law. Using creative works to train generative AI fits with the long line of cases that has found that non-consumptive, technological uses of creative works in ways that are unrelated to the expressive content of those works are transformative fair uses, such as Authors Guild v. Google and Kelly v. Arriba Soft. Moreover, the most recent Supreme Court ruling on fair use, Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, supports this conclusion. As we commented upon the decision’s release, the Warhol case focus on the specific way a follow-on use compares with the original use of a work indicates that training generative AI on creative works is transformative and should be fair use. This is because the use of copyrighted works for AI training has a fundamentally different purpose from the original aesthetic purposes of those works.

Copyright protection for AI outputs subject to significant human creative input

We believe that creative works produced with the assistance of generative AI tools should only be eligible for protection where they contain a significant enough degree of human creative input to justify protection, just like when creators use any other mechanical tools in the production of their works. The Supreme Court considered the relationship between artists and their tools vis-a-vis copyright over 100 years ago in Burrow-Giles v. Sarony, holding that copyright protects the creativity that human artists’ incorporate into their works, not the work of machines. While determining which parts of a work are authored by a human when using generative AI will not always be clear, this issue is not fundamentally different from any other situation where we have to determine the authorship of individual parts of works that are created without AI assistance.

Additionally, we believe that developers of generative AI tools should not receive copyright protection over the outputs of those tools. Copyright law already provides enough incentives to encourage development of these tools by protecting code, and extending protection to their outputs is unnecessary to encourage innovation and investment in this space.

Infringement should be determined using the substantial similarity test

We believe that the substantial similarity standard that already exists in copyright law is sufficient to address where AI outputs infringe on other works. The debate about how copyright should apply to generative AI has often been cast in all-or-nothing terms — does something infringe on pre-existing copyrights or not? The answer to this question is certainly that generative AI can infringe on other works, but just as easily it may not. As with any other question about the substantial similarity between two works, these issues will be highly fact specific, and we cannot automatically say whether works produced by generative AI tools infringe or not.

Creators should be able to express their preferences

In general, we believe there is value in methods that enable individuals to to signal their preferences for how their works are shared in the context of generative AI. In our community consultations, we heard general support for preference signals, but there was no consensus in how best to do this. Opt-ins and opt-outs may be one way, but we do not believe they need to be required by US copyright law; instead, we would like to see voluntary schemes, similar to approaches to web scraping, which allow for standardized expression of these preferences without creating strict barriers to usage in cases where it may be appropriate.

Transparency is necessary to build trust — Copyright is only one lens through which to consider AI regulation

We urge caution and flexibility in any approach to regulating generative AI through copyright. We believe that copyright policy can guide the development of generative AI in ways that benefit all, but that overregulation or inappropriate regulation can hurt both the technology and the public. For example, measures that improve transparency into AI models can build trust in AI models by allowing outside observers to “look under the hood” to investigate how they work. But these measures should not be rooted in copyright law. Copyright is just one lens through which we can view generative AI, and it is ill equipped to deal with many of the social harms that concern us and many others. Attempting to use copyright to solve all of these issues may have unintended consequences and ultimately do more harm than good.

We are happy to see the Copyright Office seeking out guidance on these many difficult questions. We will have to wait to see what comes from this, but we will hope for the best, and continue to engage our community so we can more fully understand what role generative AI should play in building the commons and serving the public good.

Read CC’s full submission to the Copyright Office >

The post CC Responds to the United States Copyright Office Notice of Inquiry on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Announcing CC’s Open Infrastructure Circle appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

CC Licenses make it possible to share content legally and openly. Over the past 20 years, they have unlocked approximately 3 billion articles, books, research, artwork, and music. They’re a global standard and power open sharing on popular platforms like Wikipedia, Flickr, YouTube, Medium, Vimeo, and Khan Academy.

CC’s Legal Tools are a free and reliable public good. Yet most people are unaware that their infrastructure and stewardship takes a lot of money and work to maintain.

We need to secure immediate and long term funding for the CC licenses and CC0 public domain tool, which are key to building a healthy commons. We’re facing many challenges and threats to the commons–libraries are under attack, misinformation is rampant, and climate change threatens us all. CC is one of the few nonprofit, mission-driven organizations fighting to ensure we have a sound legal infrastructure backing open ecosystems, so that culture and knowledge are shared in order to foster understanding and find equitable solutions to our world’s most pressing challenges.

We need support from like-minded funders to champion sharing practices and tools that oppose the enclosure of the commons.

That’s why we’re launching the Open Infrastructure Circle (OIC) — an initiative to obtain annual or multi-year support from foundations, corporations, and individuals for Creative Commons’ core operations and license infrastructure.

With consistent funding, we can resolve “technical debts” (years of work we’ve had to put on hold due to underfunding!) and make the CC Licenses more user-friendly and accessible to our large, global community. The world has changed a lot since the CC Licenses were first created in 2002, and we want to ensure they stay relevant and easy to use going forward.

We are grateful to our early Open Infrastructure Circle supporters, including the William + Flora Hewlett Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Paul and Iris Brest.

Sign up to join OIC with a recurring gift! Or reach out to us for more information about OIC at development@creativecommons.org.

Thank you for considering joining the Open Infrastructure Circle and contributing to the legal infrastructure of the open web.

The post Announcing CC’s Open Infrastructure Circle appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post CC and Communia Statement on Transparency in the EU AI Act appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act will be discussed at a key trilogue meeting on 24 October 2023 — a trilogue is a meeting bringing together the three bodies of the European Union for the last phase of negotiations: the European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament. CC collaborated with Communia to summarize our views emphasizing the importance of a balanced and tailored approach to regulating foundation models and of transparency in general. Additional organizations that support public interest AI policy have also signed to support these positions.

Statement on Transparency in the AI Act

The undersigned are civil society organizations advocating in the public interest, and representing knowledge users and creative communities.

We are encouraged that the Spanish Presidency is considering how to tailor its approach to foundation models more carefully, including an emphasis on transparency. We reiterate that copyright is not the only prism through which reporting and transparency requirements should be seen in the AI Act.

General transparency responsibilities for training data

Greater openness and transparency in the development of AI models can serve the public interest and facilitate better sharing by building trust among creators and users. As such, we generally support more transparency around the training data for regulated AI systems, and not only on training data that is protected by copyright.

Copyright balance

We also believe that the existing copyright flexibilities for the use of copyrighted materials as training data must be upheld. The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market and specifically its provisions on text-and-data mining exceptions for scientific research purposes and for general purposes provide a suitable framework for AI training. They offer legal certainty and strike the right balance between the rights of rightsholders and the freedoms necessary to stimulate scientific research and further creativity and innovation.

Proportionate approach

We support a proportionate, realistic, and practical approach to meeting the transparency obligation, which would put less onerous burdens on smaller players including non-commercial players and SMEs, as well as models developed using FOSS, in order not to stifle innovation in AI development. Too burdensome an obligation on such players may create significant barriers to innovation and drive market concentration, leading the development of AI to only occur within a small number of large, well-resourced commercial operators.

Lack of clarity on copyright transparency obligation

We welcome the proposal to require AI developers to disclose the copyright compliance policies followed during the training of regulated AI systems. We are still concerned with the lack of clarity on the scope and content of the obligation to provide a detailed summary of the training data. AI developers should not be expected to literally list out every item in the training content. We maintain that such level of detail is not practical, nor is it necessary for implementing opt-outs and assessing compliance with the general purpose text-and-data mining exception. We would welcome further clarification by the co-legislators on this obligation. In addition, an independent and accountable entity, such as the foreseen AI Office, should develop processes to implement it.

Signatories

The post CC and Communia Statement on Transparency in the EU AI Act appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Making AI Work for Creators and the Commons appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

On the eve of the CC Global Summit, members of the CC global community and Creative Commons held a one-day workshop to discuss issues related to AI, creators, and the commons. The community attending the Summit has a long history of hosting these intimate discussions before the Summit begins on critical and timely issues.

Emerging from that deep discussion and in subsequent conversation during the three days of the Summit, this group identified a set of common issues and values, which are captured in the statement below. These ideas are shared here for further community discussion and to help CC and the global community navigate uncharted waters in the face of generative AI and its impact on the commons.

Background considerations

- Recognizing that around the globe the legal status of using copyright protected works for training generative AI systems raises many questions and that there is currently only a limited number of jurisdictions with relatively clear and actionable legal frameworks for such uses. We see the need for establishing a number of principles that address the position of creators, the people building and using machine learning (ML) systems, and the commons, under this emerging technological paradigm.

- Noting that there are calls from organized rightholders to address the issues posed by the use of copyrighted works for training generative AI models, including based on the principles of credit, consent, and compensation.

- Noting that the development and deployment of generative AI models can be capital intensive, and thus risks resembling (or exacerbating) the concentration of markets, technology, and power in the hands of a small number of powerful for-profit entities largely concentrated in the United States and China, and that currently most of the (speculative) value accrues to these companies.

- Further noting that, while the ability for everyone to build on the global information commons has many benefits, the extraction of value from the commons may also reinforce existing power imbalances and in fact can structurally resemble prior examples of colonialist accumulation.

- Noting that this issue is especially urgent when it comes to the use of traditional knowledge materials as training data for AI models.

- Noting that the development of generative AI reproduces patterns of the colonial era, with the countries of the Global South being consumers of Northern algorithms and data providers.

- Recognizing that some societal impacts and risks resulting from the emergence of generative AI technologies need to be addressed through public regulation other than copyright, or through other means, such as the development of technical standards and norms. Private rightsholder concerns are just one of a number of societal concerns that have arisen in response to the emergence of AI.

- Noting that the development of generative AI models offers new opportunities for creators, researchers, educators, and other practitioners working in the public interest, as well as providing benefits to a wide range of activities across other sectors of society. Further noting that generative AI models are a tool that enables new ways of creation, and that history has shown that new technological capacities will inevitably be incorporated into artistic creation and information production.

Principles

We have formulated the following seven principles for regulating generative AI models in order to protect the interests of creators, people building on the commons (including through AI), and society’s interests in the sustainability of the commons:

- It is important that people continue to have the ability to study and analyse existing works in order to create new ones. The law should continue to leave room for people to do so, including through the use of machines, while addressing societal concerns arising from the emergence of generative AI.

- All parties should work together to define ways for creators and rightsholders to express their preferences regarding AI training for their copyrighted works. In the context of an enforceable right, the ability to opt out from such uses must be considered the legislative ceiling, as opt-in and consent-based approaches would lock away large swaths of the commons due to the excessive length and scope of copyright protection, as well as the fact that most works are not actively managed in any way.

- In addition, all parties must also work together to address implications for other rights and interests (e.g. data protection, use of a person’s likeness or identity). This would likely involve interventions through frameworks other than copyright.

- Special attention must be paid to the use of traditional knowledge materials for training AI systems including ways for community stewards to provide or revoke authorisation.

- Any legal regime must ensure that the use of copyright protected works for training generative AI systems for noncommercial public interest purposes, including scientific research and education, are allowed.

- Ensure that generative AI results in broadly shared economic prosperity – the benefits derived by developers of AI models from access to the commons and copyrighted works should be broadly shared among all contributors to the commons.

- To counterbalance the current concentration of resources in the the hands of a small number of companies these measures need to be flanked by public investment into public computational infrastructures that serve the needs of public interest users of this technology on a global scale. In addition there also needs to be public investment into training data sets that respect the principles outlined above and are stewarded as commons.

In keeping with CC’s practice to provide major communications related to the 2023 Global Summit held in Mexico City in English and Spanish, following is the text of this post originally created in English translated to Spanish

Hacer que la IA funcione para los creadores y los bienes comunes

En vísperas de la Cumbre Global CC, los miembros de la comunidad global CC y Creative Commons celebraron un taller de un día para discutir cuestiones relacionadas con la IA, los creadores y los bienes comunes. La comunidad que asiste a la Cumbre tiene una larga historia de albergar estas discusiones íntimas antes de que comience la Cumbre sobre temas críticos y oportunos.

Como resultado de esa profunda discusión y de la conversación posterior durante los tres días de la Cumbre, este grupo identificó un conjunto de cuestiones y valores comunes, que se recogen en la siguiente declaración. Estas ideas se comparten aquí para una mayor discusión comunitaria y para ayudar a CC y a la comunidad global a navegar por aguas inexploradas frente a la IA generativa y su impacto en los bienes comunes.

Consideraciones preliminares

- Reconociendo que en todo el mundo el estatus legal del uso de obras protegidas por derechos de autor para entrenar sistemas generativos de IA plantea muchas preguntas y que actualmente solo hay un número limitado de jurisdicciones con marcos legales relativamente claros y viables para tales usos. Vemos la necesidad de establecer una serie de principios que aborden la posición de los creadores, las personas que construyen y utilizan sistemas de aprendizaje automático y los bienes comunes, bajo este paradigma tecnológico emergente.

- Señalando que hay llamados de titulares de derechos organizados para abordar los problemas que plantea el uso de obras protegidas por derechos de autor para entrenar modelos de IA generativa, incluso basados en los principios de crédito, consentimiento y compensación.

- Observando que el desarrollo y despliegue de modelos generativos de IA puede requerir mucho capital y, por lo tanto, corre el riesgo de asemejarse (o exacerbar) la concentración de mercados, tecnología y poder en manos de un pequeño número de poderosas entidades con fines de lucro concentradas en gran medida en los Estados Unidos y China, y que actualmente la mayor parte del valor (especulativo) corresponde a estas empresas.

- Señalando además que, si bien la capacidad de todos para aprovechar los bienes comunes globales de información tiene muchos beneficios, la extracción de valor de los bienes comunes también puede reforzar los desequilibrios de poder existentes y, de hecho, puede parecerse estructuralmente a ejemplos anteriores de acumulación colonialista.

- Señalando que esta cuestión es especialmente urgente cuando se trata del uso de materiales de conocimientos tradicionales como datos de entrenamiento para modelos de IA.

- Señalando que el desarrollo de la IA generativa reproduce patrones de la era colonial, siendo los países del Sur Global consumidores de algoritmos y proveedores de datos del Norte.

- Reconocer que algunos impactos y riesgos sociales resultantes del surgimiento de tecnologías de IA generativa deben abordarse mediante regulaciones públicas distintas de los derechos de autor, o por otros medios, como el desarrollo de estándares y normas técnicas. Las preocupaciones de los titulares de derechos privados son sólo una de una serie de preocupaciones sociales que han aparecido en respuesta al surgimiento de la IA.

- Señalando que el desarrollo de modelos generativos de IA ofrece nuevas oportunidades para creadores, investigadores, educadores y otros profesionales que trabajan en el interés público, además de brindar beneficios a una amplia gama de actividades en otros sectores de la sociedad. Señalando además que los modelos generativos de IA son una herramienta que permite nuevas formas de creación, y que la historia ha demostrado que inevitablemente se incorporarán nuevas capacidades tecnológicas a la creación artística y la producción de información.

Principios

Hemos formulado los siguientes siete principios para regular los modelos de IA generativa con el fin de proteger los intereses de los creadores, las personas que construyen sobre los bienes comunes (incluso a través de la IA) y los intereses de la sociedad en la sostenibilidad de los bienes comunes:

- Es importante que la gente siga teniendo la capacidad de estudiar y analizar obras existentes para crear otras nuevas. La ley debería seguir dejando espacio para que las personas lo hagan, incluso mediante el uso de máquinas, al tiempo que aborda las preocupaciones sociales que aparecen por el surgimiento de la IA generativa.

- Todas las partes deberían trabajar juntas para definir formas para que las personas creadoras y quienes son titulares de derechos expresen sus preferencias con respecto a la capacitación en IA para sus obras protegidas por derechos de autor. En el contexto de un derecho exigible, la capacidad de hacer un “opt out” de tales usos debe considerarse el límite legislativo, ya que los enfoques basados en la aceptación voluntaria y el consentimiento bloquearían grandes sectores de los bienes comunes debido a la duración y el alcance excesivos de la protección de los derechos de autor, así como el hecho de que la mayoría de las obras no están siendo activamente gestionadas.

- Además, todas las partes también deben trabajar juntas para abordar las implicaciones para otros derechos e intereses (por ejemplo, protección de datos, uso de la imagen o identidad de una persona). Esto probablemente implicaría intervenciones a través de marcos distintos del derecho de autor.

- Se debe prestar especial atención al uso de materiales del conocimiento tradicional para entrenar sistemas de IA, incluidas formas para que los custodios de las comunidades proporcionen o revoquen la autorización.

- Cualquier régimen legal debe garantizar que se permita el uso de obras protegidas por derechos de autor para entrenar sistemas generativos de IA con fines no comerciales de interés público, incluidas la investigación científica y la educación.

- Garantizar que la IA generativa dé como resultado una prosperidad económica ampliamente compartida: los beneficios que obtienen los desarrolladores de modelos de IA del acceso a los bienes comunes y a las obras protegidas por derechos de autor deben compartirse ampliamente entre quienes contribuyen a los bienes comunes.

- Para contrarrestar la actual concentración de recursos en manos de un pequeño número de empresas, estas medidas deben ir acompañadas de inversión pública en infraestructuras computacionales públicas que satisfagan las necesidades de los usuarios de interés público de esta tecnología a escala global. Además, también es necesario invertir públicamente en sets de datos de entrenamiento que respeten los principios descritos anteriormente y se administren como bienes comunes.

The post Making AI Work for Creators and the Commons appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Generative AI and Creativity: New Considerations Emerge at CC Convenings appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel” by Jennryn Wetzler for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

This week, Creative Commons (CC) convened 100+ participants during two events in New York City to discuss the important issues surrounding generative artificial intelligence (AI), copyright, and creativity.

For many years, we at CC have been examining the interplay between copyright and generative AI, exploring ways in which this technology can foster creativity and better sharing, i.e. sharing that is inclusive, equitable, reciprocal, and sustainable — and it is through this lens that we strive to tackle some of the most critical questions regarding the potential of generative AI tools for creators, cultural heritage institutions, and the general public.

In search of answers we have been holding community consultations over the past months to consider how best to maximize the public benefits of AI, to address concerns with how AI systems are trained and used, and to probe how AI will affect the commons. These two NYC events come within the scope of these wider consultations aimed at assisting us in taking action with informed intention.

On 12 September, we ran a workshop at the offices of Morrison Foerster to unpack the multiple issues that arise once generative AI enters the creativity cycle. If all creativity remixes the past — which needs to be responsibly preserved and cared for — is generative AI a game changer? This was the question an interdisciplinary mix of participants approached with insight and empathy throughout the afternoon’s dynamic sessions. History teems with examples of how humans dealt with technological disruptions in the past (from the printing press and oil painting to photography), yet many participants pointed to the need to think differently and imagine new structures for AI to deliver on its promise to enhance the commons. Issues around attribution, bias, transparency, agency, artistic identity and intent, democratization of AI, and many others, peppered the discussions in small and large groups. While no definite pathways emerged, participants embraced the uncertainty and relished the prospect of generative AI being used for the common good.

The conversations flowed through the following day’s symposium, Generative AI and the Creativity Cycle, at the Engelberg Center at New York University. 100 participants attended the event, which brought together experts from various fields — including law, the arts, cultural heritage, and AI technology — speaking on seven panels covering a wide range of issues at the nexus of creativity, copyright, and generative AI.

Running like red threads across the panels, here are some of the key themes that surfaced throughout the day’s lively conversations:

- Transparency: This requirement was often cited as a precondition for society to build trust in generative AI. Transparency was deemed essential in the datasets, algorithms and models themselves, as well as in AI systems in general. Similarly, a focus on the ways users of AI content could be transparent about their processes was also needed. This tied closely to notions of attribution and recognizing machine input into creative processes.

- Attribution (or similar notions of recognition, credit, or acknowledgement): This feature reflects CC’s emphasis on better sharing: nurturing a fair and equitable sharing ecosystem that celebrates and connects creators.

- Bias: The problem of bias in AI models as well as the inequalities they perpetuate and compound came up in most if not all sessions. The imperative to address bias was raised alongside calls for greater diversity and inclusion, as is already undertaken in data decolonization efforts.

- Economic fairness: Several discussions pointed to a need for fair remuneration, distributive justice, and a universal basic income, as well as employment protection for creators.

- Copyright issues (both on the input/training and output levels): While some speakers suggested a sense of loss of control due to a lack of copyright-based permission or consent, others reiterated the fundamental right for anyone to read and absorb knowledge including through machine-automated means.

- A multi-pronged approach: Given the multifaceted nature of the challenges raised by generative AI, many speakers highlighted the need to engage on multiple levels to ensure responsible developments in AI. This tied in with the need for adequate incentives and support for open sharing, a sustainable open infrastructure, culture as a public good, sharing in the public interest, all in order to prevent further enclosures of the commons.

- Collaboration: Collaborative creation with machines as well as with other humans could give rise to a “remix culture 2.0,” where generative AI as a tool could assist in the emergence of new forms of creativity through “amalgamated imagination.”

Although the above summary does not do justice to the depth and thoughtfulness of the event’s discussions, it does give a flavor of the topics at stake and should help inform those thinking about AI development, regulation, and its role in supporting better sharing of knowledge and culture in our shared global commons.

A special thank you to our workshop participants and symposium speakers and moderators. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to connect with many of you and share diverse perspectives on this complex topic. We are grateful to Morrison Foerster for supporting the workshop, donating space and resources. We’d also like to thank our lead symposium sponsor Akin Gump as well as the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy for publicly hosting these important conversations.

View symposium video recordings

Subscribe to CC’s email newsletter to stay informed about all our work with AI, culture and creativity, and more.

Continue the discussion on AI and the commons at the CC Global Summit during 3–6 Oct 2023 in Mexico City >

Check out these images from different panels during the symposium!

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel A” by Anna Tumadóttir for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel B” by Brigitte Vézina for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel C” by Brigitte Vézina for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel D” by Brigitte Vézina for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

“Generative AI & the Creative Cycle Panel E” by Brigitte Vézina for Creative Commons is licensed via CC BY 4.0.

The post Generative AI and Creativity: New Considerations Emerge at CC Convenings appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post An Open Letter from Artists Using Generative AI appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

“Better Sharing With AI” by Creative Commons was generated by the DALL-E 2 AI platform with the text prompt “A surrealist painting in the style of Salvador Dali of a robot giving a gift to a person playing a cello.” CC dedicates any rights it holds to the image to the public domain via CC0.

As part of Creative Commons’ ongoing community consultation on generative AI, CC has engaged with a wide variety of stakeholders, including artists and content creators, about how to help make generative AI work better for everyone.

Certainly, many artists have significant concerns about AI, and we continue to explore the many ways they might be addressed. Just last week, we highlighted the useful roles that could be played by new tools to signal whether an artist approves of use of their works for AI training.

At the same time, artists are not homogenous, and many others are benefiting from this new technology. Unfortunately, the debate about generative AI has too often become polarized and destructive, with artists who use AI facing harassment and even death threats. As part of the consultation, we also explored how to surface these artists’ experiences and views.

Today, we’re publishing an open letter from over 70 artists who use generative AI. It grew from conversations with an initial cohort of the full signatory list, and we hope it can help foster inclusive, informed discussions.

Signed by artists like Nettrice Gaskins, dadabots, Rob Sheridan, Charlie Engman, Tim Boucher, illustrata, makeitrad, Jrdsctt, Thomas K. Yonge, BLAC.ai, Deltasauce, and Cristóbal Valenzuela, the letter reads in part:

“We write this letter today as professional artists using generative AI tools to help us put soul in our work. Our creative processes with AI tools stretch back for years, or in the case of simpler AI tools such as in music production software, for decades. Many of us are artists who have dedicated our lives to studying in traditional mediums while dreaming of generative AI’s capabilities. For others, generative AI is making art more accessible or allowing them to pioneer entirely new artistic mediums. Just like previous innovations, these tools lower barriers in creating art—a career that has been traditionally limited to those with considerable financial means, abled bodies, and the right social connections.”

Read the full letter and list of signatories. If you would like to have your name added to this list and are interested in follow-up actions with this group, please sign our form. You can share the letter with this shorter link: creativecommons.org/artistsailetter

While the policy issues here are globally relevant, the letter is addressed to Senator Chuck Schumer and the US Congress in light of ongoing hearings and “Insight Fora” on AI hosted in the USA. Next week, Schumer is hosting one of these Fora, but the attendees are primarily from tech companies; the Motion Picture Association of America and the Writers Guild of America are invited, but there are no artists using generative AI specifically.

We also invited artists to share additional perspectives with us, some of which we’re publishing here:

Nettrice Gaskins said: “Generative AI imaging is a continuation of creative practices I learned as a college student, in my computer graphics courses. It’s the way of the future, made accessible to us in the present, so don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Elizabeth Ann West said: “Generative AI has allowed me to make a living wage again with my writing, allowing me to get words on the page even when mental and chronic health conditions made doing so nearly impossible. I published 3 books the first year I had access to Davinci 3. Generative AI allows me to work faster and better for my readers.”

JosephC said: “There must be room for nuance in the ongoing discussion about machine-generated content, and I feel that the context vacuum of online discourse has made it impossible to talk and be heard when it comes to the important details of consent, the implications of regulation, and the prospects of making lives better. We need to ensure that consenting creatives can see their work become part of something greater, we need to ensure pioneering artists are free to express themselves in the medium that gives them voice, and we need to be mindful of the wishes of artists who desire to have their influence only touch the eyes and ears and minds of select other humans in the way they want. Opportunities abound; let us work together to realize them.”

Tim Simpson said: “Generative AI is the photography of this century. It’s an incredible new medium that has immense potential to be leveraged by artists, particularly indie artists, to pursue artistic visions that would have been completely infeasible for solo artists and small teams just a year ago. Open source AI tools are immensely important to the development of this medium and making sure that it remains available to the average person instead of being walled off into monopolized corporate silos. Many of the regulatory schemes that are being proposed today jeopardize that potential, and I strongly urge congress to support measures that keep these tools open and freely available to all.”

Rob Sheridan said: “As a 25 year professional artist and art director, I’ve adapted to many shifts in the creative industry, and see no reason to panic with regards to AI art technology itself….I fully understand and appreciate the concerns that artists have about AI art tools. With ANY new technology that automates human labor, we unfortunately live under a predatory capitalism where corporations are incentivized to ruthlessly cut human costs any way they can, and they’ve made no effort to hide their intentions with AI (how many of those intentions are realistic and how many are products of an AI hype bubble is a different conversation). But this is a systemic problem that goes well beyond artists; a problem that didn’t begin with AI, and won’t end with AI. Every type of workforce in America is facing this problem, and the solutions lie in labor organizing and in uniting across industries for major systemic changes like universal healthcare and universal guaranteed income. Banning or over-regulating AI art tools might plug one small hole in the leaky dam of corporate exploitation, but it closes a huge potential doorway for small creators and businesses.”

The post An Open Letter from Artists Using Generative AI appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Exploring Preference Signals for AI Training appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>

“Choices” by Derek Bruff, here cropped, licensed via CC BY-NC 2.0.

One of the motivations for founding Creative Commons (CC) was offering more choices for people who wish to share their works openly. Through engagement with a wide variety of stakeholders, we heard frustrations with the “all or nothing” choices they seemed to face with copyright. Instead they wanted to let the public share and reuse their works in some ways but not others. We also were motivated to create the CC licenses to support people — artists, technology developers, archivists, researchers, and more — who wished to re-use creative material with clear, easy-to-understand permissions.

What’s more, our engagement revealed that people were motivated to share not merely to serve their own individual interests, but rather because of a sense of societal interest. Many wanted to support and expand the body of knowledge and creativity that people could access and build upon — that is, the commons. Creativity depends on a thriving commons, and expanding choice was a means to that end.

Similar themes came through in our community consultations on generative artificial intelligence (AI*). Obviously, the details of AI and technology in society in 2023 are different from 2002. But the challenges of an all-or-nothing system where works are either open to all uses, including AI training, or entirely closed, are a through-line. So, too, is the desire to do so in a way that supports creativity, collaboration, and the commons.

One option that was continually raised was preference signaling: a way of making requests about some uses, not enforceable through the licenses, but an indication of the creators’ wishes. We agree that this is an important area of exploration. Preference signals raise a number of tricky questions, including how to ensure they are a part of a comprehensive approach to supporting a thriving commons — as opposed to merely a way to limit particular ways people build on existing works, and whether that approach is compatible with the intent of open licensing. At the same time, we do see potential for them to help facilitate better sharing.

What We Learned: Broad Stakeholder Interest in Preference Signals

In our recent posts about our community consultations on generative AI, we have highlighted the wide range of views in our community about generative AI.

Some people are using generative AI to create new works. Others believe it will interfere with their ability to create, share, and earn compensation, and they object to current ways AI is trained on their works without express permission.

While many artists and content creators want clearer ways to signal their preferences for use of their works to train generative AI, their preferences vary. Between the poles of “all” and “nothing,” there were gradations based on how generative AI was used specifically. For instance, they varied based on whether generative AI is used

- to edit a new creative work (similar to the way one might use Photoshop or another editing program to alter an image),

- to create content in the same category of the works it was trained on (i.e., using pictures to generate new pictures),

- to mimic a particular person or replace their work generally, or

- to mimic a particular person and replace their work to commercially pass themselves off as the artist (as opposed to doing a non-commercial homage, or a parody).

Views also varied based on who created and used the AI — whether researchers, nonprofits, or companies, for instance.

Many technology developers and users of AI systems also shared interest in defining better ways to respect creators’ wishes. Put simply, if they could get a clear signal of the creators’ intent with respect to AI training, then they would readily follow it. While they expressed concerns about over-broad requirements, the issue was not all-or-nothing.

Preference Signals: An Ambiguous Relationship to a Thriving Commons

While there was broad interest in better preference signals, there was no clear consensus on how to put them into practice. In fact, there is some tension and some ambiguity when it comes to how these signals could impact the commons.

For example, people brought up how generative AI may impact publishing on the Web. For some, concerns about AI training meant that they would no longer be sharing their works publicly on the Web. Similarly, some were specifically concerned about how this would impact openly licensed content and public interest initiatives; if people can use ChatGPT to get answers gleaned from Wikipedia without ever visiting Wikipedia, will Wikipedia’s commons of information continue to be sustainable?

From this vantage point, the introduction of preference signals could be seen as a way to sustain and support sharing of material that might otherwise not be shared, allowing new ways to reconcile these tensions.

On the other hand, if preference signals are broadly deployed just to limit this use, it could be a net loss for the commons. These signals may be used in a way that is overly limiting to expression — such as limiting the ability to create art that is inspired by a particular artist or genre, or the ability to get answers from AI systems that draw upon significant areas of human knowledge.

Additionally, CC licenses have resisted restrictions on use, in the same manner as open source software licenses. Such restrictions are often so broad that they cut off many valuable, pro-commons uses in addition to the undesirable uses; generally the possibility of the less desirable uses is a tradeoff for the opportunities opened up by the good ones. If CC is endorsing restrictions in this way we must be clear that our preference is a “commons first” approach.

This tension is not easily reconcilable. Instead, it suggests that preference signals are by themselves not sufficient to help sustain the commons, and should be explored as only a piece of a broader set of paths forward.

Existing Preference Signal Efforts

So far, this post has spoken about preference signals in the abstract, but it’s important to note that there are already many initiatives underway on this topic.

For instance, Spawning.ai has worked on tools to help artists find if their works are contained in the popular LAION-5B dataset, and decide whether or not they want to exclude them. They’ve also created an API that enables AI developers to interoperate with their lists; StabilityAI has already started accepting and incorporating these signals into the data they used to train their tools, respecting artists’ explicit opt-ins and opt-outs. Eligible datasets hosted on the popular site Hugging Face also now show a data report powered by Spawning’s API, informing model trainers what data has been opted out and how to remove it. For web publishers, they’ve also been working on a generator for “ai.txt” files that signals restrictions or permissions for the use of a site’s content for commercial AI training, similar to robots.txt.

There are many other efforts exploring similar ideas. For instance, a group of publishers within the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is working on a standard by which websites can express their preferences with respect to text and data mining. The EU’s copyright law expressly allows people to opt-out from text and data mining through machine-readable formats, and the idea is that the standard would fulfill that purpose. Adobe has created a “Do Not Train” metadata tag for works generated with some of its tools, Google has announced work to build an approach similar to robots.txt, and OpenAI has provided a means for sites to exclude themselves from crawling for future versions of GPT.

Challenges and Questions in Implementing Preference Signals

These efforts are still in relatively early stages, and they raise a number of challenges and questions. To name just a few:

- Ease-of-Use and Adoption: For preference signals to be effective, they must be easy for content creators and follow-on users to make use of. How can solutions be ease-to-use, scalable, and accommodate different types of works, uses, and users?

- Authenticating Choices: How best to validate and trust that a signal has been put in place by the appropriate party? Relatedly, who should be able to set the preferences — the rightsholder for the work, the artist who originally created it, both?

- Granular Choices for Artists: So far, most efforts have been focused on enabling people to opt-out of use for AI training. But as we note above, people have a wide variety of preferences, and preference signals should also be a way for people to signal that they are OK with their works being used, too. How might signals strike the right balance, enabling people to express granular preferences, but without becoming too cumbersome

- Tailoring and Flexibility Based on Types of Works and Users: We’ve focused in this post on artists, but there are of course a wide variety of types of creators and works. How can preference signals accommodate scientific research, for instance? In the context of indexing websites, commercial search engines generally follow the robots.txt protocol, although institutions like archivists and cultural heritage organizations may still crawl to fulfill their public interest missions. How might we facilitate similar sorts of norms around AI?

As efforts to build preference signals continue, we will continue to explore these and other questions in hopes of informing useful paths forward. Moreover, we will also continue to explore other mechanisms necessary to help support sharing and the commons. CC is committed to more deeply engaging in this subject, including at our Summit in October, whose theme is “AI and the Commons.”

If you are in New York City on 13 September 2023, join our symposium on Generative AI & the Creativity Cycle, which focuses on the intersection of generative artificial intelligence, cultural heritage, and contemporary creativity. If you miss the live gathering, look for the recorded sessions.

The post Exploring Preference Signals for AI Training appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Understanding CC Licenses and Generative AI appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>“CC Icon Statue” by Creative Commons, generated in part by the DALL-E 2 AI platform. CC dedicates any rights it holds to this image to the public domain via CC0.

Many wonder what role CC licenses, and CC as an organization, can and should play in the future of generative AI. The legal and ethical uncertainty over using copyrighted inputs for training, the uncertainty over the legal status and best practices around works produced by generative AI, and the implications for this technology on the growth and sustainability of the open commons have led CC to examine these issues more closely. We want to address some common questions, while acknowledging that the answers may be complex or still unknown.

We use “artificial intelligence” and “AI” as shorthand terms for what we know is a complex field of technologies and practices, currently involving machine learning and large language models (LLMs). Using the abbreviation “AI” is handy, but not ideal, because we recognize that AI is not really “artificial” (in that AI is created and used by humans), nor “intelligent” (at least in the way we think of human intelligence).

CC licensing and training AI on copyrighted works

Can you use CC licenses to restrict how people use copyrighted works in AI training?

This is among the most common questions that we receive. While the answer depends on the exact circumstances, we want to clear up some misconceptions about how CC licenses function and what they do and do not cover.

You can use CC licenses to grant permission for reuse in any situation that requires permission under copyright. However, the licenses do not supersede existing limitations and exceptions; in other words, as a licensor, you cannot use the licenses to prohibit a use if it is otherwise permitted by limitations and exceptions to copyright.

This is directly relevant to AI, given that the use of copyrighted works to train AI may be protected under existing exceptions and limitations to copyright. For instance, we believe there are strong arguments that, in most cases, using copyrighted works to train generative AI models would be fair use in the United States, and such training can be protected by the text and data mining exception in the EU. However, whether these limitations apply may depend on the particular use case.

It’s also useful to look at this from the perspective of the licensee — the person who wants to use a given work. If a work is CC licensed, does that person need to follow the license in order to use the work in AI training? Not necessarily — it depends on the specific use.

- To the extent your AI training is covered by an exception or limitation to copyright, you need not rely on CC licenses for the use.

- To the extent you are relying on CC licenses to train AI, you will need to follow the relevant requirements under the licenses.

Another common question we hear is “Does complying with CC license conditions mean you’re always legally permitted to train AI on that CC-licensed work?”

Not necessarily — it is important to note here that CC licenses only give permission for rights granted by copyright. They do not address where other laws may restrict training AI, such as privacy laws, which are always a consideration where material contains personal data and are not addressed by copyright licensing. (Many kinds of personal data are not covered by copyright at all, but may still be covered by privacy-related regulations.)

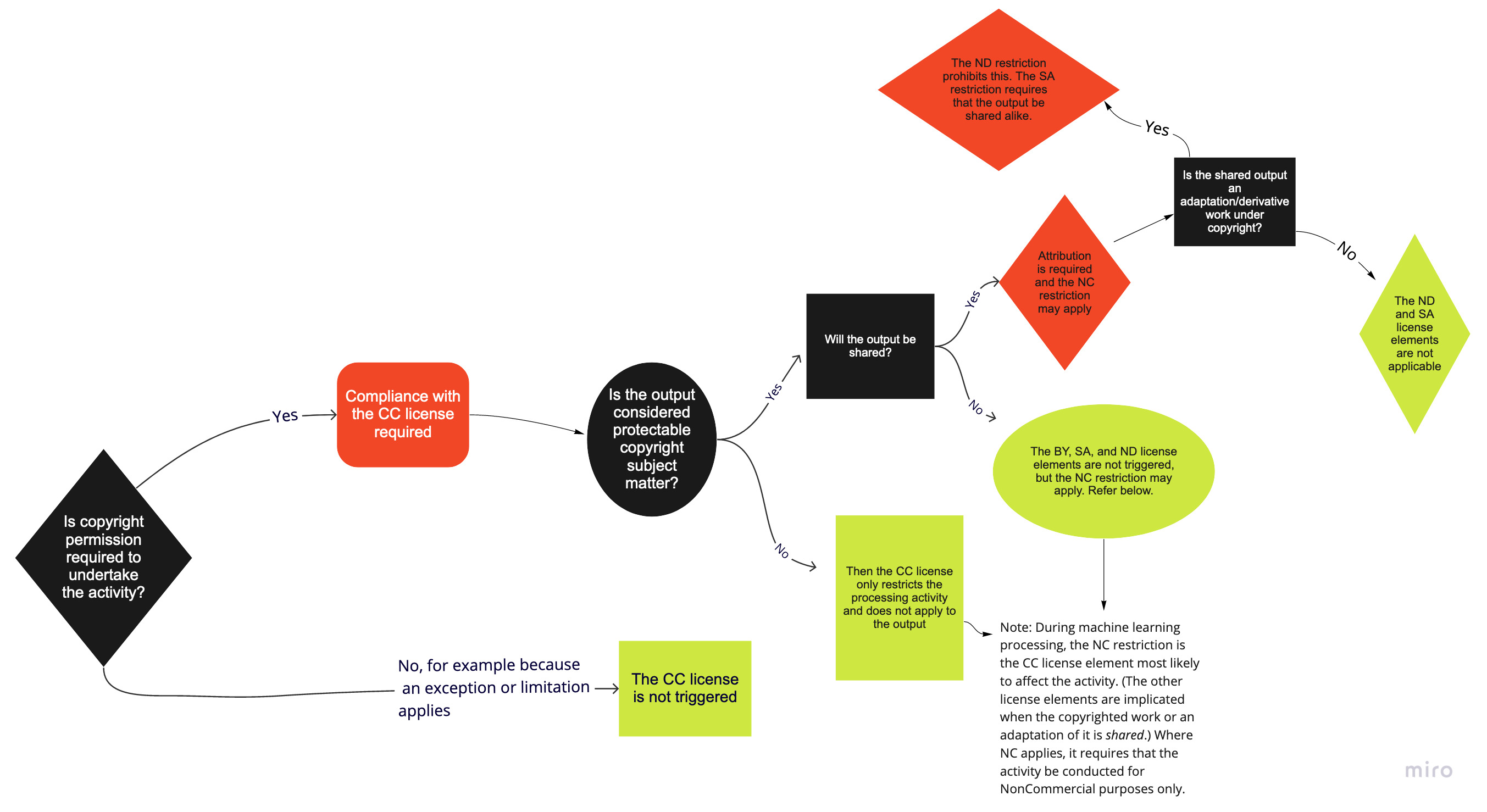

For more explanation, see our flowchart regarding the CC licenses in this context, and read more in our FAQ on AI and CC licenses.

CC Licenses and outputs of generative AI

In the current context of rapidly developing AI technologies and practices, governments scrambling to regulate AI, and courts hearing cases regarding the application of existing law, our intent is to give our community the best guidance available right now. If you create works using generative AI, you can still apply CC licenses to the work you create with the use of those tools and share your work in the ways that you wish. The CC license you choose will apply to the creative work that you contribute to the final product, even if the portion produced by the generative AI system itself may be uncopyrightable. We encourage the use of CC0 for those works that do not involve a significant degree of human creativity, to clarify the intellectual property status of the work and to ensure the public domain grows and thrives.

Beyond copyright

Though using CC licenses and legal tools for training data and works produced by generative AI may address some legal uncertainty, it does not solve all the ethical concerns raised, which go far beyond copyright — involving issues of privacy, consent, bias, economic impacts, and access to and control over technology, among other things. Neither copyright nor CC licenses can or should address all of the ways that AI might impact people. There are no easy solutions, but it is clear we need to step outside of copyright to work together on governance, regulatory frameworks, societal norms, and many other mechanisms to enable us to harness AI technologies and practices for good.

We must empower and engage creators

Generative AI presents an amazing opportunity to be a transformative tool that supports creators — both individuals and organizations — provides new avenues for creation, facilitates better sharing, enables more people to become creators, and benefits the commons of knowledge, information, and creativity for all.

But there are serious concerns, such as issues around author recognition and fair compensation for creators (and the labor market for artistic work in general), the potential flood of AI-generated works on the commons making it difficult to find relevant and trustworthy information, and the disempowering effect of the privatization and enclosure of AI services and outputs, to name a few.

For many creators, these and other issues may be a reason not to share their works at all under any terms, not just via CC licensing. CC wants AI to augment and support commons, not detract from it, and we want to see solutions to these concerns to avoid AI turning creators away from contributing to the commons altogether.

Join us

We believe that trustworthy, ethical generative AI should not be feared, but instead can be beneficial to artists, creators, publishers, and to the public more broadly. Our focuses going forward will be:

- To develop and share principles, best practices, guidance, and training for using generative AI to support the commons. We don’t have all the answers — or necessarily all the questions — and we will work collaboratively with our community to establish shared principles.

- To continue to engage our community and broaden it to lift up diverse, global voices and find ways to support different types of sharing and creativity.

- Additionally, it is imperative that we engage more with AI developers and services to increase their support for transparency and ethical, public-interest tools and practices. CC will be seeking to collaborate with partners who share our values and want to create solutions that support a thriving commons.

For over two decades we have stewarded the legal infrastructure that enables open sharing on the web. We now have an opportunity to reimagine sharing and creativity in this new age. It is time to build new infrastructure that supports better sharing with generative AI.

We invite you to join us in this work, as we continue to openly discuss, deliberate, and take action in this space. Follow along with our blog series on AI, subscribe to our newsletter, support our work, or join us at one of our upcoming events. We’re particularly excited to welcome our community back in-person to Mexico City in October for the CC Global Summit, where the theme is focused squarely on AI & the commons.

The post Understanding CC Licenses and Generative AI appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>The post Style, Copyright, and Generative AI Part 2: Vicarious Liability appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>What is vicarious liability?

One of the claims raised in the suit against Stable Diffusion and Midjourney is that AI tools should be held vicariously liable for copyright infringement because their users can use the systems to create infringing works. Typically, legal liability arises where someone directly commits an act that harms another person in such a way that the law can hold that person responsible for their actions. This is “direct liability.” If a distracted driver hits a cyclist, the cyclist might ask the court to make the driver pay any damages, because the driver is directly liable for the accident. Normally, third parties are not considered responsible for the acts of other people. So, the law would probably not hold anyone but the driver liable for the accident — not a passenger, and not even one who was helping to navigate or who had asked the driver to make the trip. And unless the car was faulty, the manufacturer of the car would not be liable either, even though if no one had made the car the accident would not have happened: the car could have been used without harming anyone, but in this case it was the driver who made it cause harm.

“Art Meets Technology” by Stephen Wolfson for Creative Commons was generated by the Midjourney AI platform with the text prompt “an artist using a mechanical art tool to create a painting realistic 4k.” CC dedicates any rights it holds to the image to the public domain via CC0.

Under some circumstances, however, U.S. law may hold third parties liable for the harmful acts committed by other people. One such legal doctrine is “vicarious liability” — when a third party has essentially used another party to commit the harmful act. Courts in the United States have found vicarious liability in copyright law when two conditions are met: (1) the third party has the ability to supervise and control the acts of the person who committed the direct infringement, and (2) the third party has an “obvious and direct” financial benefit from the infringing activity. Notably, vicarious liability for infringement only occurs where another party has become directly liable for copyright infringement. If there was no direct liability for infringement at all, a third party cannot be held responsible.

Vicarious liability requires a relationship between the third party and the person committing the direct infringement, where the third party retains some control over the other person’s actions and where the third party economically benefits from those actions — for example, an employer/employee relationship.

In the US, the 9th Circuit examined the issue of control and technology-enabled vicarious copyright infringement in the specific context of search engines and credit card payment processors in Perfect 10 v. Amazon.com and Perfect 10 v. Visa. Perfect 10 v. Amazon.com involved Google image search linking to images owned by Perfect 10 on third-party websites. The court held that Google did not have the ability to control what those third-party websites were doing, even though it had control over its website index and its search results. Similarly, in Perfect 10 v. Visa, the 9th Circuit held that Visa was not liable for infringement committed by websites that hosted content belonging to Perfect 10, even though Visa processed credit card payment for those websites. The court wrote that “just like Google [in Perfect 10 v. Amazon.com], Defendants could likely take certain steps that may have the indirect effect of reducing infringing activity on the Internet at large. However, neither Google nor Defendants has any ability to directly control that activity.” In both cases, the relationship between the third party and the potential infringement was not close enough to sustain a vicarious infringement claim because of a lack of control.

Turning to the second element, obvious and direct financial benefit, the 9th Circuit has written that this is satisfied where infringement acts as a draw for users to the service, and that there is a direct causal link between the infringing activities at issue and the financial benefit to the third party. In another case involving Perfect 10, Perfect 10 v. Giganews, the 9th Circuit held that Usenet provider, Giganews, did not derive a direct financial benefit from users who distributed Perfect 10’s content on their servers, even though Giganews charged a subscription fee to those users. Because it wasn’t clear that users were drawn to Giganews for its ability to distribute Perfect 10’s content, the court was unwilling to hold Giganews vicariously liable for the actions of its users.

Should generative AI tools be liable for the actions of their users?

How do these elements of control and financial benefit apply in the context of generative AI? Normally, no one would argue that the creators of art tools like paintbrushes or digital editing tools like Photoshop or Final Cut Pro should be responsible when their users use their tools for copyright infringement. Their creators cannot directly control how people use them and they do not clearly benefit from copyright infringement conducted with them. That seems uncontroversial. The question, however, is more complex with GAI because these platforms have the ability to deny service to users who misuse their services and may derive their profits/funding based on how many people use them. That said, tools like Stable Diffusion or Midjourney do not have the practical ability to prevent infringing uses of their tools. Like in Perfect 10 v. Amazon.com and Perfect 10 v. Visa, they do not directly control the ways people use their tools. While they could deny access to users who misuse the tools, it seems impossible to stop users from entering generic terms as text prompts to ultimately recreate copyrighted works. Furthermore, as I discussed in my previous post on style and copyright, there are legitimate reasons for people to use other artists’ copyrighted works, such as fair use. So, banning users from prompting tools with “in the style of” or “like another copyrighted work” would be overbroad, harming legitimate uses while trying to stop illegitimate ones, because we can only tell what is legitimate or not based on the facts of individual situations.

As with any other general purpose art tool, there simply doesn’t seem to be a way to prevent all users from using GAI in ways that raise concerns under copyright, without shutting down the tools themselves, and stopping all uses, legitimate or not. Compare with something like automatic content filtering tools. These tools may be good at finding and automatically removing access to copyrighted material that is posted online, but even the best systems identify many false positives, removing access to permissible or authorized uses along with the infringing ones. In doing so, they can harm legitimate and beneficial uses that copyright law’s purpose is designed to support.

Moreover, GAI tools like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney do not necessarily have an “obvious and direct financial benefit” from copyright infringement conducted by users of their platforms. In the case of Stable Diffusion and Midjourney specifically, that link doesn’t appear to exist. They make the same amount of money from users, regardless of how they put the tools to use. Since neither platform advertises itself as a tool for infringement, both discourage copyright-infringing uses as parts of the terms of service, and neither profits directly from copyright infringement, there does not seem to be a direct causal link between these hypothetical infringing users and Stable Diffusion or Midjourney’s funding.

Furthermore, it is not clear that copyright infringement is a draw for users to these services. As mentioned above, simply creating works in the style of another artist does not necessarily mean those works are infringing. Moreover, there may be legitimate reasons to use artists’ names as text prompts. For example, a parody artist may need to use the name of their subject to create their parodies, and these works would have a strong argument that they are permissible under fair use in the United States.

For other GAI tools, the question of whether there is obvious and direct financial benefit from copyright infringement will be case-dependent. Nevertheless, the link between the ability to use the tools for copyright infringement and whether this is a draw for users to the GAI tools will likely be, at best, unclear in most circumstances. And without a causal link between the financial benefit to the GAI creator and infringement conducted by users, this element will not be met.

Ultimately, while it’s easy to understand why artists would feel threatened by generative AI tools being able to mimic their artistic styles, copyright law should not be a barrier to the legitimate use and development of these tools. While it may make sense for the law to step in and prevent specific instances of infringement, copyright should not prevent the legitimate use and development of generative AI technologies, especially when they can help to expand and enhance human creativity. And while there may not be any perfect solutions to these issues, we need to figure out norms and best practices that can allow these promising new technologies to develop and thrive, while also respecting the rights and concerns of artists and the public interest in access to knowledge and culture. For now, we will watch and see what happens in the courts, and continue to encourage dialog and discussion in this area.

The post Style, Copyright, and Generative AI Part 2: Vicarious Liability appeared first on Creative Commons.

]]>